Visions of the Floating World: Ethnicity and representation in artificially generated images of Japanese American taiko

Article by Gregory Wada

(Author’s copy of a piece in the Young Buddhist Editorial.)

Keywords: AI Art, Viewership, Performativity, Representation, Asian America, Taiko

Abstract: Media Studies is an interdisciplinary field that seeks to understand the ways in which social, cultural, economic, and political life is structured by media. This piece examines artificially generated images of taiko players to ask questions about both the technology and society that decides what ethnicity looks like. Taiko is explored as an organic expression of Japanese American and Asian American identity that is heavily influenced by media portrayal.

The New Ukiyo-e

The style of woodblock printing known as ukiyo-e became popular among the merchant class, lowest of the social classes though growing in economic might, in the Tokugawa shogunate that ruled the Edo Period (1615-1868). Following technological innovations in 1765 that allowed for the production of prints in multiple colors, the distinctive style of bold prints featured beautiful women, famous actors, heightened scenes of the everyday, landscapes, and historical events. The term ukiyo can mean “sorrowful world,” as in the cycle of rebirth, but it conveniently can be homophonically understood as “floating world,” a term associated with the transitory pleasures of urban life during the time.

Ukiyo-e was “low class” art, with centers of production in red-light and entertainment districts, but it was incredibly transformative in how everyday people interacted with visual art. It is an example of art created at the intersections of technology and society. Far from the trope of the tortured artist working in isolation, the production of woodblock prints involved a coordinated effort between a publisher (Hanmoto), image designer (Eshi), wood carver (Horishi), and print-maker (Surishi). Through the print-making process, many nearly identical images were also produced in mass - there were perhaps around eight-thousand prints of “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” produced, for instance. Ukiyo-e represents a particular moment of democratization in art, one that might serve as a useful vantage for a similar movement in digital art today.

Like many internet-era denizens, I was captivated by the ability of artificial intelligence to generate images from natural language prompts. If you haven’t already tried it, consider a quick session on Craiyon (www.craiyon.com) for yourself. Like ukiyo-e, these images are made possible by a team of creators - the developers of the artificial intelligence, the distributors of the technology to an online audience, and the language inputs of the user. The result, too, are heightened scenes of the online world we have come to know and inhabit - they are images that cut through the specifics of a google image search to return something essential about the state of the (online) world around us.

The full effects of this technology on society and art are yet to be realized, but the potential is great. Take the title image for this article, for instance. I was able to generate an image that fit a simple idea for cover art that would be rather difficult (for me) to execute by brush or by stylus. In this case, it created art where there might otherwise be none. I stopped here, but a user could further manipulate the image and integrate it into various “digital assets.” While not replacing the designer, it might become a tool into the designer’s workflow. Both the creativity of the userbase and the innovations of the technology make this an exciting development to follow.

However, as we’ve seen in other iterations of artificial intelligence, as much as they have revolutionary potential, such technologies also have the ability to reenforce existing inequality and power structures. The output of machine learning is conditional on the data it is fed, or as the saying goes, “garbage in, garbage out.” In the same way that chatbots learn racist language behavior from the way humans interact online, image generators have to contend with the fact that the net sum of our online images represent a particular set of viewerships. Who holds the camera? Who uploads the images? Who creates the memes?

This piece is certainly not a condemnation of the technology or of its users. It is the simple reflection of a digital Buddhist scrolling through the forms (and forums) of a new “floating world.” I hope that through these types of meditations, we might control the technology, rather than the other way around.

Choosing an Artistic Subject: Portraits of Performers

Ukiyo-e artists often chose subjects from everyday life - a whole subgenera, popular in Osaka, was exclusively devoted to portraits of actors. For my study, I decided to select an artistic subject that would be both familiar to me and be conductive to a reflection on viewership. For me, the choice was clear - taiko! Though taiko, as music, must be heard and experienced beyond its visuality, its rendering as visual media is one that I wish to explore deeper. For those interested in this problem, in taiko or more generally, I recommend Deborah Wong’s (2019, pp. 29-53) chapter “Looking, Listening, and Moving.”

I’ve been a taiko performer for over a decade and my experience as a performer has given me insight into the ways that cultural expressions can be interpreted in radically differently ways based on the positionally of the viewer. To one audience member, our performance made him “want to cut something in half with a katana.” Another connected our performance to the Asian American Movement and thanked us for “keeping the music alive.” Another said it’s not like the taiko they remember from growing up, but that they liked it - the songs were exciting and theatrical.

These different interpretations of a taiko performance have left me skeptical of a shared lens by which the audience experiences taiko music. I think there is heterogenous viewership, in which the same performance might convey different cultural meanings to different observers. This is not saying that meaning in art is complete arbitrary, but rather that the communication is encoded. Borrowing from a movement from a K-pop dance during a solo, for instance, elicits a difference response in those who are in-on-the-joke, and this particular reception happens to be largely structured along generational lines. In an art form born within and between Asian American experiences, it’s understandable that many references in taiko are ethnically structured, often serving as a form of embodied historical memory. Furthermore, generes in-of-themselves tend to have a self-referential set of signals understood by those who are in-the-know, such as players themselves.

Though you cannot control how music is received, whenever you go on stage to perform, you do control the signal. Everything from the happi and hachimaki you wear to the way you drop your core when you strike is up to you as a performer. A photo of a performance, however, also introduces composition from the viewer. What features are highlighted? What moments are immortalized? Take for instance a YouTube video that someone uploaded of our college group entitled, “Cute Asian Girl Plays the Drums.” The camera slowly zooms in on one of the players in the ensemble to the point of being uncomfortably close. The player is moving and reacting to the other players around her, but through the eyes of this viewer, we watch only her, intently.

The thing about the photograph, an image generated of the performer, is that many aspects of the composition are outside the control of the performer, the performer’s signal is filtered through a literal and figurative lens of the viewer. In this realization is the heart of what I want to explore. When art is performed, or made real in the world, there is a relationship between artist and viewer, that while imperfect, it conveys real or specific experiences or imaginings of the artist. When artificial images are made from the images of viewers, the artist or initial subject is further removed from the relationship.

Would these dreams within dreams erode specific meanings by their averaging, a sort of Gaultian “regression towards mediocracy?” Or could they perhaps spark new insights by drawing connections between disparate nodes in the largest network of human information? What images of taiko would the collective uploads of the internet create? To find out, I would need to book a trip to the workshop of the new ukiyo-e and find out for myself.

A Day in the Digital Workshops

Finally, the day came and I arrived to tour the print-making workshops. Specifically, I went to the free webpage for Craiyon[1] and also signed up for a free DALL-E account[2], which allows for a limited number of free images that replenish monthly (you can buy more). You, too, can do this without spending any money - the cost is being subjected to a few advertisements from the former and giving your email and phone number to the latter.

It seems that Craiyon, formerly called DALL-E Mini, is not related to DALL-E, which is the program developed by the company OpenAI. If this is already confusing, one difference is that Craiyon uses an open-source architecture, unlike OpenAI, which is a for-profit company that does not always open-source their programs[3]. OpenAI was initially a non-profit founded by Elon Musk and Sam Altman (Musk later quit), which did an about face and turned (limited) for-profit[4]. Craiyon, on the other hand was first built during a hackathon[5]. Before you pick sides, however, you should know that Craiyon uses a smaller training dataset and is lax on security, allowing for the generation of explicit imagery and the reproduction of stereotypes[6]. Great, they’re both messy and complicated dens of vice and hedonism - the perfect place to find my team of artists!

I got to take the role that might be likened to the publisher, or maybe an executive producer in today’s terms. I had some vague and/or overly specific ideas that I would tell my team of artificially intelligent algorithms to get working on, and they would typically get back to me in under two minutes[7] with a small portfolio of work, nine lower-resolution images for Craiyon[8] and four higher-resolution images in DALL-E[9] (you get four images generated for 1 “credit”). For the study presented, I gave both programs the same prompt and either selected the one I thought performed the best (when one image is displayed) or shared the whole set (when it seemed more informative).

Now, for the first time, I would like to share with you a reflective gallery of select work produced during this process. Please, come, step inside as we explore Eighteen Views of Taiko.

Exhibit Room 1: Perspectives on Style

This exhibit reflects on artistic style, or the AI’s ability to understand and replicate characteristics of the desired genre. Though, as I’ve laid out above, I am principally investigating the portrayal of ethnicity through depictions of AI generated images of taiko, this first stop is a calibration and a reflection on the (perhaps somewhat narratively contrived) theme of ukiyo-e. When I first started playing with the software, I realized that specifying genre would be a useful tool in comparing between programs and sets of images, grounding the act of viewing in a particular framework. Comparing photo-realism to impressionism to digital art, for instance, may provide us with many interpretations about genre when we wish to focus on subject. We’ll explore a few of these later, but why not start with the main metaphor of this piece?

View 1: Playing an odaiko solo on the moon, the moon is the instrument, the player celestial, ukiyo-e.

Craiyon

View 2: Playing an odaiko solo on the moon, the moon is the instrument, the player celestial, ukiyo-e.

DALL-E

This prompt is principally imaginative; it references no myth or taiko-specific knowledge of which I am aware. As ukiyo-e, both images reference the later periods, if at all. The images bear some distant resemblance to the work of Utagawa Kuniyoshi[10] (1798-1861) or Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892), the latter whose series “100 Aspects of the Moon” might be most comparable[11].

View 1 is fuzzy, not just in resolution but in commitment to form and movement - I find it most evocative if you imagine the figure’s left leg (our right) forward and the motion of the arm winding as to strike downwards and towards the middle of the image. Perhaps the player will strike the ground beneath them, which is perhaps the moon (the moon in the back may not be a literal placement). The player wears a flowing indigo kimono, reminiscent of the sky above. The placement of (imaginary) text is clearly “understanding” of this characteristic of nearly all ukiyo-e prints. From a taiko player perspective (which would be anachronistic anyway), the three-legged stool is an odd stand and I’m not exactly sure what’s going on with that tassel hanging in the bottom right. My intuition tells me this is a rendering of a kan (ring used to handle drum), but it’s placement is so off from a drum-making perspective that I instinctively refuse that interpretation. The drum is clearly tacked, though, and widest in the middle of body, a roundness that is both accurate to life and juxtaposed nicely with the moon in the sky above.

View 2 conveys the natural language prompt much clearer - the subject is making to strike the moon with a bachi. Perhaps most gratifying is the natural motion of the body, the arms are loose and extended, the movement is driven from the core. The hands are, well - the bachi might go flying - but maybe that’s what it takes to hit the moon. The player rises from dark, indigo clouds or mountains, their hakama matching in color. The gradient of color in the clouds and moon, as well as the textured ink, do give an impression of ukiyo-e, but something is deeply off, too. The outlines are too strong, the colors are too blocky. It has a very modern quality.

View 3: Ukiyo-e landscape of a taiko player playing the upright odaiko in a snowstorm

Craiyon

View 4: Ukiyo-e landscape of a taiko player playing the upright odaiko in a snowstorm

DALL-E

Similarly, this prompt reflects an imaginative theme, a depiction of playing taiko in nature. Perhaps simply by asking for this subject matter, the rendered work is a bit more reminiscent of a Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) or Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) landscape.

View 3 displays snow-covered mountains in the background and a sky full of large, heavy snowflakes. The hitting surface of the blurred taiko in the foreground is facing us, though it is relatively low to the ground, about thigh-height, and the player approaches from the right side, knees bent. Their kimono is a spring pink, perhaps not quite in season. The vermillion structures are a nice color contrast with the blues and whites of the natural landscape, though closer examination reveals an Escher-esque architecture. The feeling is again dreamlike.

View 4 depicts a clearer scene of a man (possibly with a mustache) playing a drum in the snow, surrounded on both sides by young, spindly pines. The player makes to strike with a mallet in the right hand, while muting the drum with the left hand. He is in a low stance, with the angle of the knee approaching a right angle. His textured clothes include pants and winter jacket pulled closed with an obi. He wears tekko (wrist band), but only on his right hand, and kyahan (lower leg gaiters). An interesting piece of headwear extends back behind him like the crest of a Parasaurolophus. While not playing “upright,” the stance is grounded, kinetic, believable. The act of muting the drum resonates (or I suppose the opposite) with the quieting snow, heavy flakes falling all around. The taiko depicted has a cylindrical body, where it should be wider in the middle, but perhaps most interesting is the apparent Remo (the modern drum company) tunable-head design that uses a metal ring to provide tension (though it is missing the tightening apparatus). The whole image deviates slightly from the conventions of woodblock printing - the use of the “brush” has become more pronounced - but the subject matter is similarly captivating.

Both programs were able to interpret rather esoteric prompts and connected the act of playing taiko (even without including a literal drum in the case of DALL-E) with the other subject matter in a style that approximates ukiyo-e. To avoid redundancy and to foreground the more central questions to this article, I will not not focus future commentary on these programs’ ability to produce ukiyo-e specifically, though there are a few observations to be made considering the full dataset, not all presented here.

Craiyon often produces images that include (imaginary) text, which is typically placed in a sensible location, and mostly generates images of people in kimono, reminiscent of many human subjects from across periods of ukiyo-e. The colors tend to be a bit more faded, though it can be teased to create the stark indigos and vermilions of a Hiroshige snowscape. From a distance, they have the anatomy of a woodblock print, though on close inspection they have a sort of dream-like formlessness.

DALL-E rendered much clearer subject matter, particularly when it came to the human form and its interactions. Stylistically, it had a harder time staying in genera or interpreting “ukiyo-e” meaningfully, with some results returning as photorealistic images or other styles of visual imagery. When it did produce woodblock prints, they sometimes had a Japonisme[12] quality, the European art movement inspired by Japanese aesthetics. When asked to imitate certain artists, such as Hiroshige, this was particularly pronounced. While Craiyon seems to err on the side of averaging the work of the artist you want and forgetting the subject matter described, DALL-E seems to prioritize the subject matter requested, generated from some other ether-pool of images, and then apply some aspects of the artist in question. Regardless, it is recognizably a tall order to ask the AI to interpret a particular artist’s sensibility when approaching the human form, its scale and movement.

The ability of both programs to create ukiyo-e inspired pieces is still remarkable, especially when considering the linguistic and cultural specificity requested. Although, herein lies the deeper question about art and the representation of specific experiences. Perhaps it’s time for us to move to the next room.

Exhibit Room 2: Perspectives on Mythology and History

Continuing our exploration of taiko as a subject of visual consideration, we turn now to specific moments that are remembered as myth, history, or perhaps somewhere in between. Taiko is one of those art forms with an assumed antiquity that breaks down, much like these AI images, upon closer examination. There are aspects of the material and musical culture of taiko that do stretch back hundreds to thousands of years, but ensemble taiko is a relatively young art form, dating to the 1950’s in Japan and late 1960’s in the United States. It’s also not a simple story of a translocated art form, brought by immigrants from Japan to the Americas. Taiko is practiced today in places with large Japanese diasporas in the United States, Canada, and Latin America, but it is largely the story of creating an art form in-situ, and as such it takes on the cultural understandings and politics of Asian American identity formation, particularly during the Asian American Movement in the United States.

In this exhibit, we reflect on moments of myth and history of particular significance to North American Taiko players, from the mythological origins of taiko in the distant past to the historical memories of the art in America.

View 5: Ame no Uzumi performing a comedic dance atop a wine barrel to lure Amaterasu from the cave, thereby returning light to the world. Ukiyo-e print.

Craiyon

View 6: Ame no Uzumi performing a comedic dance atop a wine barrel to lure Amaterasu from the cave, thereby returning light to the world. Ukiyo-e print.

DALL-E

This prompt asks the algorithms to depict a moment from the Shinto legend of Amaterasu and the Cave[13], in which Ame no Uzumi (see Wong 2019, pp. 73-74 for a taiko player’s interpretation), goddess of the dawn, mirth, and the arts, dances comedically atop a barrel in order to coax the hiding Amaterasu out of the cave so that the sun might shine again upon the world. In many taiko playing communities in North America, this legend is known and referenced as a sort of evidence of taiko’s spiritual, if not material, antiquity. Beyond the reach of history, it can be leveraged, as myths often are, to define the scope of a community. “We are all descendant of the first drumbeat” can be a unifying statement, helping people to see commonality and shared cause, though it can also act as a form of erasure, wresting power from locally-specific histories, particularly when spoken through the powers that be. As taiko moves more into the spaces of the dominant society, these types of erasure may serve to perpetuate extant inequalities and power structures (much as AI art may replicate such disparity in the world) by circumventing the cultural context and politics of the artists.

View 5 shows a rather floating image of two figures in motion. There is a pull between the figures, both regard each other. Uzumi, I presume to be the figure on the left in the green, seems to be dancing, a hand raised towards the head in a sort of pose reminiscent of Awa Odori. Perhaps she is making way for Amaterasu to join her, giving her a turn to dance on the barrel. Amaterasu’s robes flow behind her - she is moving towards the center of action. I presume the almost-Japanese text in the upper left would tell us the full story.

View 6 shows Uzumi in the midst of her comical dance, hinting at a somewhat ribald or scandalous mood. Her head is pitched back and she exposes her bare thighs, opening her legs towards Amaterasu peeking from the cave. Uzumi seemingly supports herself by holding onto a tree above as she sits on the somewhat formless barrel - perhaps a large storage container turned upside down. Her face is an abstract collection of shapes, reflecting her mood or perhaps her divine nature. Amaterasu, head covered, is similar abstracted, being drawn into the scene from hiding near the left side of the frame.

Both hint as aspects of a particular tellings, but your reading may depend on your familiarity or interpretation of the story, which is honestly not outside the norm for religious or mythological art. Without knowing the characters, “The School of Athens” might as well be the Avengers. Perhaps we should move to examine those histories, whose specifics are still lived and material.

View 7: Woodblock print of San Francisco Taiko Dojo playing Soko-Bayashi, a song dedicated to the Issei pioneers and the enduring spirit of the immigrant experience.

Craiyon

View 8: Woodblock print of San Francisco Taiko Dojo playing Soko-Bayashi, a song dedicated to the Issei pioneers and the enduring spirit of the immigrant experience.

DALL-E

Grandmaster Seiichi Tanaka is often credited as the father (or grandfather, as he now jokes)[14] of North American Taiko. His story has become a sort of origin story among many North American Taiko players. Tanaka sensei met Kumiko, a Japanese American artist, while she was in Japan, and eventually immigrated to the United States with her[15]. As an artist, Kumiko actually made her own prints depicting taiko[16], which capture a lived experience worth mentioning in a piece filled with artificially generated ones.

As the story goes, Tanaka sensei attended the Northern California Cherry Blossom Festival and found it to be missing the sound of Japanese matsuri[17]. He borrowed a drum from a local temple for a parade entry, which was well-received by the Issei[18], the generation of immigrants who came to the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Seeing the potential for taiko in America, Tanaka returned to Japan to study with Daihachi Oguchi, credited with the invention of kumidaiko (ensemble drumming), and the group Oedo Sukeroku, formed from competitive Obon drummers. He returned to the United States and opened the San Fransisco Taiko Dojo, though they did not have drums at first and trained using tires[19] until the wine-barrel drum was invented and spread along Japanese American Buddhist networks (more on that later). Tanaka sensei dedicated his first song to those Issei pioneers, calling it “Soko Bayashi,[20]” “Soko” being the nickname given to San Francisco by Japanese immigrants[21]. This origin story is sometimes mistaken as a simple story of musical translocation. Many young players who know the framework of the story assume that he initially brought taiko with him from Japan, however the story is nuanced and deeply mediated by multiple immigration histories within the Japanese American diaspora.

View 7 depicts some sort of taiko performance, though any human forms are unrecognizable, substituted instead with abstract patches of color, perhaps a representation of motion. The image is actually divided into two halves depicting a similar scene - I like the interpretation that the left side is from the performer’s perspective, looking out over the drums towards the audience, while the right panel shows the performance from the audience’s perspective, looking at players in motion behind their drums. The up-facing odaiko or ohiradaiko, seemingly depicted here, is certainly reminiscent of some of San Fransisco Taiko Dojo’s songs, including “Soko Bayashi” in some arrangements. In this interpretation, we simultaneously consider the musical moment from both sides of the stage. We see that both are in motion, reflections of each other. Or perhaps what is performed on stage in a taiko performance is a reflection of the communities that sustain the art.

View 8 is a series of prints reminiscent of album art or perhaps posters for a concert or folkloric celebration. They display text that is both clear and nonsenseical, resembling letters from the Roman, Greek, and Cyrillic alphabets as well as approximations of Chinese characters. There are specific references to San Francisco - the Golden Gate Bridge and Alcatraz can be seen in the background of the first image and the steep hills of the city form the background of the second and possibly third image. They are charmingly joyful. In the first image, three people raise indecipherable objects to the sky, facing away from us and towards the bay, while a Miyake-style drum sits in the foreground. In the second image, a small ensemble of performers play drums and dance, their movements synchronized. The third image, a monochrome print, similarly features two rows of performers - the front row seems to be dancing, even using a common Bon Odori movement, while the players in the back might be playing a naname style of drumming. The last image is colorful with a naturalistic placement of people who mostly have instruments - they are playing together.

For a song dedicated to the immigrant experience and written for a community of Japanese Americans who persisted through Incarceration, these depictions of “Soko Bayashi” all work well with an interpretation of music-as-community. It might be worth mentioning that “Soko Bayashi” is a stage-performance piece characterized by rolling oroshi[22] at the start and a driving ostinato backbeat that carries through the rest of the song structure and solos, until Sensei’s solo on the tetto (a metal tube instrument sometimes called canon) near the end, where he deconstructs the tempo and reflects on the falling, fading sounds of the introduction. It is an energetic piece, but usually in the way that is captivating to watch, not necessarily to dance alongside. The images somehow capture the idea of the piece, perhaps even reflect on San Francisco Taiko Dojo’s origins at the Northern California Cherry Blossom Festival, which is what cover art is meant to do. But how do you capture the feeling of a song in its visual depiction?

In one of Kumiko’s prints[23], a horse, mythical creature, and wild energy surround an odaiko with a head that has stars like the night sky. The player, who bears a resemblance to Tanaka sensei, stands with arms aloft, about to play or having just finished playing. This whole scene is as a fan on display above an ikebana arrangement in a small vase. The loud and the quiet are reflections of each other.

View 9:

Monochrome print of an odaiko with a drum head that is the night sky. Surrounding the drum are a horse, mythical bird, and wild energy. A taiko player stands with arms reached to the sky, about to play or having just finished playing the drum. This whole scene is on a fan displayed above an ikebana arrangement in a small vase.

DALL-E (inspired by a Kumiko Tanaka piece, not pictured in this article)

Japanese American Buddhist Taiko

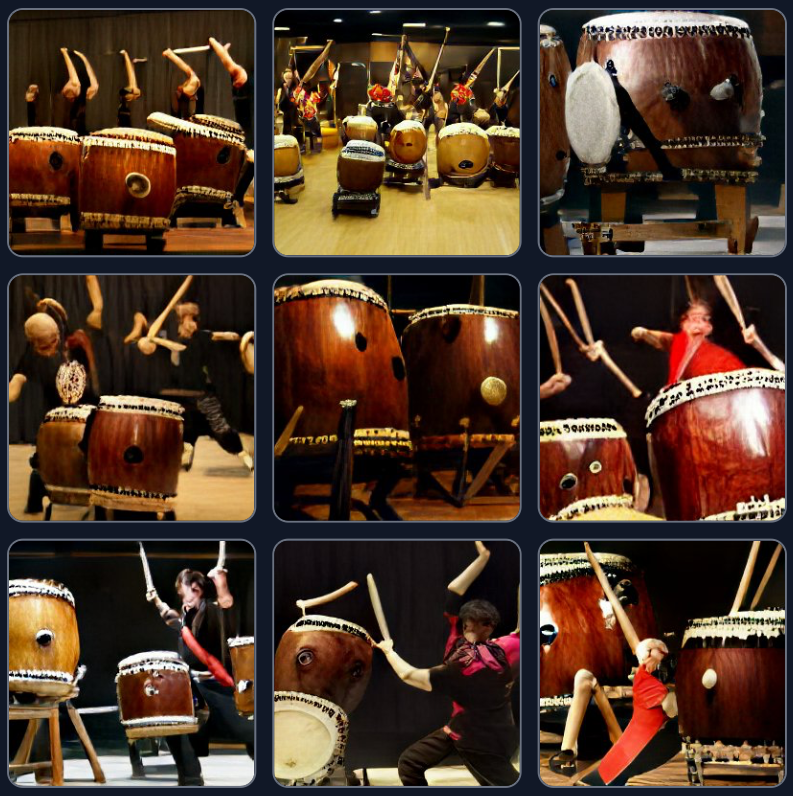

View 10: Japanese American Buddhist Taiko

Craiyon

View 11: Japanese American Buddhist Taiko

DALL-E

View 10 is a series of nine images depicting people with Edo-period clothing and hairstyles in various positions playing taiko or what appears to be dengaku processions, Shinto ceremonies that brought fortune with rice planting, calmed the forces of nature, or served other religious functions. Other than the chudaiko in a beta position (facing upwards) in the upper middle image, the taiko used are more believably of the same time period - shimedaiko and possibly an okedo. (The middle image may be of a miyadaiko, a tacked drum comparable to chudaiko used in Buddhist ritual, but the body is also not visible.) It reads as Japanese but not as American or even particularly Buddhist, let alone the intersections of these identities. The compositions are decently tasteful and feel like ukiyo-e.

View 11 is a series of four images, related in design aesthetic, reminiscent of perhaps the Polish School of Posters[24] or Avant-garde lithography. The style of dress is similarly Edo-Period, though not naturalistically so - it looks like a mid-twentieth century’s recollection of a folk past. The colors are bold and the figures are expressive, though rather serious. The first (left to right) image looks like it could grace the cover of a Smithsonian Folkway Recording. The figure in the back appears to be singing as well as playing. The figure in front has hands clenched expressively, possibly singing as well. The second image invents a style of play where a solid-body drum mounted on a bipod is played like a tsutsumi, though off the shoulder. Though it may be an interpretive leap, the third image appears to be a man tying a rope-tension drum, a bit large to be a typical shimedaiko, but a bit narrow to be an okedo. As anyone who has tied shime knows, the process can be a bit involved, which is captured perfectly by the player’s scrunched face and comically erect hachimaki. The last image likens someone playing a Miyake-like style to a samurai - his bachi cut like a blade and he carries polearms or shinai, strapped to his body. He looks like a student of mine - and I have a feeling this student would appreciate the warrior likening. For some Japanese Americans, samurai imagery still resonates in a personal way that weaves and orbits around white America’s typified samurai, accepting some aspects of The Last Samurai while holding some community-specific ones, perhaps Usagi Yojimbo. (Stan Sakai[25], author of Usagi Yojimbo, considers himself sansei, born to a Nissei father and Japanese mother in Kyoto, where his father was stationed after WWII. He grew up in Hawai’i.)

Reverend Masao Kodani[26] of Senshin Buddhist Temple in Los Angeles was one of the architects of North American Taiko. Kinnara Taiko, named after the celestial musicians[27] of Buddhist and Hindu mythology, was started as a temple music program in 1969, after a legendary post-Obon jam session. In order to have a taiko group, you need a good number of drums, which were prohibitively expensive to buy from Japan - most temples would only have one or a very limited number. Kinnara solved this problem by making their own - first crudely stretching a skin over a tack barrel and later developing the wine barrel taiko, now ubiquitous in North American Taiko and beyond. Performing at the temple and in the larger community, their performance was markedly ethnic in a society that was actively and violently wrestling with issues of racial equality. Sansei Japanese Americans growing up in the 1970’s lived with the (often unspoken) legacy of the wartime Incarceration, which obliterated communities and intergenerational wealth, left families in upheaval, and of which the dominant society would rather forget. It was a time of new and continued wars in Asia in which American bombs tore apart Asian places and American film proliferated anti-Asian sentiments. It was also a time when young students of color in American universities began an intellectual resistance to American Imperialism, starting the Third World Movement and engaging in solitary-building identity projects, such as the Black Liberation Movement and the Asian American Movement.

Taiko was very much a part of this time, and I believe that to be a student of taiko, one must also be a student of history. With the growth of taiko in North America, Rev. Kodani was insistent that it was important that what they played at Kinnara was Japanese-American-Buddhist-Taiko. (I will stylize it without hyphens to mean roughly the same identity set, but the hyphens were an important part of the discourse at the time.) This statement of identity serves as a set of resistances that push back against 1) a growing Japanophilia or perhaps new Japonisme (J-cool) that does not recognize the Americanness of extant Japanese Americans, 2) white appropriation of their music as intangible world heritage devoid of culturally specific understandings, and 3) erasure of Buddhist peoples and philosophies deeply embedded in the history and practice of taiko. Taiko is a performance of ethnicity, but one that Rev. Kodani asserts is as American as any other. As he once put it, sushi is American - if he, an American, eats sushi, then sushi is American. Central to this argument is that Japanese American culture is American culture.

This assertion problematizes what must now be a glaring contraction in the conceit of this very article - what does it mean to make an ukiyo-e print of Japanese American Buddhist Taiko? What unites these two arts, separated in time and space, other than an appeal to an aesthetic, in other words, viewership. Why do taiko players wear happi other than a reference to Obon, whether directly (a personal connection to the material culture of Obon in the United States) or indirectly (that’s what everyone since the Bon-daiko drummers from Oedo Sukeroku have worn). I don’t think people should stop wearing happi anymore than I think people should stop taking pictures of taiko - but I am suggesting that these sorts of productions grow beyond our control and, once part of the hive-mind, the forces of subversion and reference become part of the structure’s vocabulary.

Artificial intelligence may mirror a process that happens naturally in the neural net of human culture - the typification of unique phenomena into operational types[28]. As such, they may be mirrors into our own frameworks of understanding, or as powerful new tools, they may accelerate or accentuate certain modes of viewing or understanding. As both image consumers and image creators, what can we do to push back - to bring back to the foreground the local and specific? Perhaps one simple strategy is to develop a critical eye, to interrogate and consider - to build reflection, creation, and interpretation into how we view.

Scrolling through the community forums, I found a post tagged “ethnic.” Great, another traveler exploring ethnicity in the digital age, right? Well, sort of - I clicked and found images generated from sexualized language meant to generate “pretty,” “stunning,” and “exotic” “ethnic” women. It was the “pretty Asian drummer” YouTube video, replicated again. Intentionally or not, it weaponizes viewership towards the erasure or willful forgetting of violences that still loom right beneath the surface. It’s hard to see that and not recall the 2021 Atlanta shootings[29] or wonder if the conviction for the murder of Hae Min Lee, recently vacated[30], would have played out differently if police took the investigation of alternate suspects more seriously - one of whom may have went on to harm others[31]. Even without obvert violence, what would it be like for those most scrutinized by oppressive viewerships to be granted self-determination of their own visual and aesthetic experiences? In the end, we often can’t control what we see, nor might we want to, but at the least we might move forward through the world with both new lenses to view and new senses to interrogate.

Before we leave the floating world, though, let’s take a few more glances into their fleeting, accidental moments.

Exhibit Room 3: Things as They Are and Will Be

In the previous rooms, we took long, interpretive looks at AI generated imagery of taiko and explored their mediated relationships with genre and history. We took time to consider the act of viewing and interpreting these pieces. In this last exhibit space, we will move more quickly and explore outside the parameters of the previous study to broaden our perspectives of this intersection of culture and technology. We will drop the comparison between algorithms for every prompt, selecting images at will in a final, visual meditation.

View 12: Detailed Ukiyo-e landscape of the Obon festival in San Jose Japantown. A large crowd is gathered around a taiko group performing in front of the Hondo.

DALL-E

San Jose Obon is one of the largest Obon celebrations in Northern California. Home to San Jose Taiko[32] and the Chidori Band, the Obon is notable for its live music[33]. For years now, San Jose Taiko, in collaboration with the temple, has invited collegiate taiko groups to perform at the festival, bringing collegiate taiko players into this vital community space. As evening draws near, the Chidori band plays an Enka set. The day’s performances culminate with a set by San Jose Taiko, one of their larger annual sets that draws a huge crowd on closed-off 5th Street. Afterwards, for Bon Odori, dancers move in unison to the live music produced by the Chidori Band and San Jose Taiko.

This DALL-E image does not quite get the location right, though the building sort of looks like a combination of the hondo, the gym, and the classrooms across the street. The feel is not entirely off, though - telephone poles and old trees line a wide boulevard, leaving an open stretch of indigo sky as the evening sets in and it’s time for the dancing to begin. It is close enough to my memory to elicit a response, though the specifics of the moment are being drawn from somewhere within, not presented in the image. Have you been to San Jose Obon? Another Obon? Do you see your experiences in this image?

View 13: Claude Monet impressionist painting of a taiko player.

DALL-E

The French painter Claude Monet (1840-1926) is known as a founder of Impressionism, which like Ukiyo-e, depicted everyday life of an urban population, though with an emphasis on capturing the qualities of light. What would a Monet painting of taiko look like?

Here we see a European-presenting woman in a long-sleeved happi and hakama holding an okedo (presumably - many of the AI images placed the drum in the correct location but did not depict the strap that holds it across the shoulder). She appears to be outdoors, perhaps in a park or the countryside. Light glimmers off her face and the head of the drum. She appears to be happy.

There is currently a growing taiko scene in Europe (centers in the U.K. and Germany). In what ways does taiko change when represented in an impressionist painting? In this imagined anachronism, what ways do mythologizing about art and culture collide?

View 14: Futurism. In the year 2073, Bakuhatsu Taiko Dan performs "Space Utage," a futuristic taiko performance that irreverently blends history with innovation. Dark background with popping neon colors.

DALL-E

In my old collegiate taiko group, in which we confront “generational” change rapidly, we used to joke about what the distant future of our club might look like. There was a joke that we would get invited back to perform in our twilight years, but that our signature song “Utage,” written by my friend and roommate-at-the-time Taiyo Onoda, would be “Space Utage.” In this fiction, we struggle to keep up but still have the drive to play. I think anyone who has passed through our program since 2013 knows that energetic rush after hearing the first few notes.

Well, finally, here is an image of that future. North American Taiko is just over 50 years old - what will it look like in another 50 years? When we think about the future, in what ways is it different than thinking about the past?

View 15: taiko

Craiyon

View 16: taiko

DALL-E

View 17: 和太鼓

DALL-E

What if you just ask the AI to generate an image of taiko? And why didn’t I start here? (Okay, I might have and that’s what got me thinking about representation in visual imagery. As you can see, they are a bit grotesque to dwell on.)

This simple prompt gives an insight into what each program interprets the word taiko to represent. Taiko (literally “drum”) has come to represent the style of drumming, the entire artform. It refers to both an instrument and a genre. When given the English word, Craiyon returns images of a taiko performance and DALL-E returns images of the drums. The performance that Craiyon renders is made-for-stage, with wood floors and a black backdrop. The amalgamations of limbs and blurred faces that are the players are (horrifically) not identifiable, though the overall feeling I get is white performance. The drums are tacked, but also have weird and misplaced organs, like the players. Of the drums that DALL-E returns, one has a single row of tacks that look more or less believable until you look at the drums in the background. The other two appear to have the Remo-style metal tuning rings - though how tension would be applied to those chudaiko represented is questionable. It baffles me how this relatively rare style of drum manufacture in a discontinued line of products has come to dominate DALL-E’s vision of taiko. It’s possibly just an artifact of the training set it used, but it may also struggle more mechanically with interpreting the regularly placed small tacks that are used on most byo-daiko (tacked drum, as opposed to rope tension). While, taiko just means drum in Japanese, wadaiko would specify a Japanese drum. I thought that giving DALL-E the kanji for wadaiko might cue it to a dataset that just includes Japanese taiko, though the results are even less related to the Japanese drum and still include the Remo-style tuning[34].

Taiko, both as a music I play and an instrument that I make, is not yet adequately represented in AI image generation. Maybe it’s an oversight, or a step on the way - or maybe it’s a good thing! There are still some things in the world that you have to know personally and intimately, that cannot be imitated by just knowledge-of, even from the vast archives of the greatest information network ever made. Whether it’s playing taiko, or studying Buddhism, or being Japanese American in this particular time and place - there are experiences that are not replicated simply by being recorded. As this is true for visual knowledge, it is also true for linguistic, aural, or other ways of existing.

View 18: Digital Art. A taiko player imagines powerful crashing waves as they play quiet notes on the drum. It is a moment of dynamic change in the piece. They carry the weight of history and the hope of tomorrow.

DALL-E

Epilogue: Words

There’s a Zen saying that I’ve carried with me since childhood that goes something like this:

“Before seeking enlightenment, mountains are mountains and rivers are rivers. Along the way to enlightenment, mountains are no longer mountains and rivers no longer rivers. Upon achieving enlightenment, mountains are again mountains and rivers are again rivers.”

I find myself coming back to this idea time and time again, as it seems to be the perfect metaphor for coming into any type of understanding - scientific, cultural, interpersonal, musical, etc. The things that we take for granted are never so simple once we interrogate them. However, through the process of examination, we come to see more clearly how they operate and there comes a time when we can come to rest in our understanding, operationally speak again of mountains and rivers. I do not take this to mean that things are as they were before, or that we are as we were before, but that we become unburdened in our understandings, which may too continue to evolve.

But there’s just a few problems with this quote, the first of which is that I didn’t learn it from a Zen master or a dharma talk - I read it on a calendar when I was a kid. Also, when I want to share the sentiment with someone, it comes off as some esoteric statement about Enlightenment rather than a metaphor for the journey to understanding. Maybe I have taken these words of wisdom for granted, so let’s go on a little journey of understanding.

This little bit of calendar wisdom is originally from the ninth century master Qingyuan Weixin, though I think it may sometimes get misattributed to Dogen’s similarly-sounding “Mountains and Rivers Sutra.” The actual quote is probably more like this, compiled and translated by Alan Watts (p. 126, 220).

老僧三十年前未參 禪時、見山是山、見水是水、及至後 夾 親見知識、有箇入處、見山不是山、見水不是水、而今得箇體歇處、依然見山 秪 是 山、見水 秪 是水

Before I had studied Zen for thirty years, I saw mountains as mountains, and waters as waters. When I arrived at a more intimate knowledge, I came to the point where I saw that mountains are not mountains, and waters are not waters. But now that I have got its very substance I am at rest. For it's just that I see mountains once again as mountains, and waters once again as waters.

The foregrounding of satori from that calendar quote is less central here, less of a catch-phrase or destination. Many people unfamiliar with Buddhism assume that our goal is to attain enlightenment. In fact, during this past summer’s “Buddhism 101” talk at the San Jose Buddhist Betsuin, a visitor asked Rev. Sakamoto what enlightenment was, to which he answered, “Don’t worry about enlightenment.” The crowd laughed at this obvious koan. “No, really!” he responded. The more you try to grasp enlightenment, the harder it is to live the dharma.

Or as Watts (p. 197) puts it:

Planned surprises are as much of a contradiction as intentional satori, and whoever aims at satori is after all like a person who sends himself Christmas presents for fear that others will forget him. One must simply face the fact that Zen is all that side of life which is completely beyond our control, and which will not come to us by any amount of forcing or wangling or cunning - stratagems which produce only fakes of the real thing.

Out of curiosity, I tried another translation. Google Translate gave me the following from the Traditional Chinese above.

Thirty years ago, when the old monk did not practice meditation, he saw that mountains were mountains and waters were waters. Later, he saw knowledge with his own eyes. He had a place to enter. He saw that mountains were not mountains, and he saw that waters were not water. Now that he has a resting place for his body, he still sees mountains and seedlings. It is a mountain, see the water, the grain is water.

Even without the work of a human interpreter, we get a new interpretation, one in which the self has faded more into to the background. It has become more of a short story. It also has the familiar nonsensical hilarity of Google Translate - like when “Jedi Council” gets interpreted as “Presbyterian Church.” In this case, the machine learning is taking 秪 to mean seedling, shoot, or grain, when it should probably read as “only” or “merely.” The last idea might be better read as, “Now that he has a place to rest, he sees mountains are merely mountains and water is merely water.”

Am I any closer to a better version of this story, through scholarship or through the use of an AI reflecting pond? What about this saying sticks so vividly in my mind?

I spent much of my childhood in Northern Utah roaming the mountains just behind our house (often to my poor mother’s worry). From the valley floor, mountains rise resolute into the sky, their varied slopes catching the light of a hundred different times of day - they are indeed mountains.

But as you run off to explore them, the landscape suddenly changes around you. In a wooded glen with a trickling creek, the air is soft and cool, and in the shade of the cliffs above you, you are enclosed, within something, not atop it. Climbing up the spine of a ridge, you move through tall grass or from bluff to bluff, and your world becomes the ground ahead of you. Sure, it may be a mountain, but you are an ant on a non-Euclidean cost surface.

However, when you get to the top, or wherever you’re going really, and sit for a moment, the mountain takes another form. In only about ten minutes of quiet, the animal world moves on from your arrival - the birds resume their noisy bustle; rodents continue their work; a bumble bee carelessly slams into you; a deer casually walk by, though you certainly would have scared it off if you were on the move.

The slope, the aspect, the geology - whatever it is that makes the mountain a mountain is present in that moment, too. It is the mountain in the distance, a slope rising high into the sky, and it is the mountain beneath your feet. It is here and there. It is a mountain.

So where does that leave me? Do I have a better way to explain this metaphor?

When you see a mountain, it is a mountain. But when you start to climb it, it is something else entirely. Coming to rest at the top, it is again a mountain.

Is this any different than where I started? Well, it’s still a mountain.

老僧三十年前未參 禪時、見山是山、見水是水、及至後 夾 親見知識、有箇入處、見山不是山、見水不是水、而今得箇體歇處、依然見山 秪 是 山、見水 秪 是水

DALL-E

Before I had studied Zen for thirty years, I saw mountains as mountains, and waters as waters. When I arrived at a more intimate knowledge, I came to the point where I saw that mountains are not mountains, and waters are not waters. But now that I have got its very substance I am at rest. For it's just that I see mountains once again as mountains, and waters once again as waters.

DALL-E

When you see a mountain, it is a mountain. But when you start to climb it, it is something else entirely. Coming to rest at the top, it is again a mountain.

DALL-E

Footnotes

2 https://labs.openai.com - also see Ramesh et al. (2022)

3 Wiggers (2022) - https://techcrunch.com/2022/05/19/when-big-ai-labs-refuse-to-open-source-their-models-the-community-steps-in/

4 Robitzski (2019) - https://futurism.com/ai-elon-musk-openai-profit

5 Bastian (2022) - https://the-decoder.com/dall-e-mini-becomes-craiyon-and-hopefully-the-confusion-stops-now/

6 Ibid.

7 DALL-E is significantly faster, usually under thirty seconds

8 Craiyon states that it is developing a higher-resolution version. It currently exports 820x1208 screenshots of which the image gets a little under two-thirds of the layout.

9 1024x1024 pixels, typically around 2MB

10 Strusiewicz (2018) - https://japanobjects.com/features/utagawa-kuniyoshi

11 Compare to “100 Aspects of the Moon: Cassia Tree Moon” (1886)

12 Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest - https://www.mfab.hu/tours/the-call-of-the-east/

13 Takiguchi (2020) - https://naokoyogitakiguchi.medium.com/when-the-sun-goddess-hid-in-the-cave-of-heaven-a-medicine-story-from-japanese-creation-myths-30b166125c32

14 I’ve seen this reported, but I heard him make the joke to a crowd at a reception recognizing his accomplishments, hosted by the Japanese Consulate General in 2017.

15 Interview of Seiichi Tanaka by Hansen and Sojin (2005b), “Coming to America” - http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/interviews/clips/436/

16 Rafu Shimpo (2020) - https://rafu.com/2020/10/obituary-kumiko-tanaka-artist-and-backbone-of-s-f-taiko-dojo/

17 Interview of Seiichi Tanaka by Hansen and Sojin (2005a), “Lack of Taiko at Cherry Blossom Festival” - http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/interviews/clips/438/

18 Interview of Seiichi Tanaka by Hansen and Sojin (2005c), “Soukou Bayashi: Dedicated to the Issei” - http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/interviews/clips/351/

19 Interview of Seiichi Tanaka by Hansen and Sojin (2005d), “Tire Dojo” - http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/interviews/clips/443/

20 Sometimes written as Sokobayashi or Soukou Bayashi. Soko is the phonetic nickname for San Francisco and Hayashi (Bayashi) is a musical accompaniment, such as for festival procession. Many traditional uses of taiko would be in the accompaniment of such events, not performed alone.

21 Interview of Seiichi Tanaka by Hansen and Sojin (2005c), “Soukou Bayashi: Dedicated to the Issei” - http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/interviews/clips/351/

22 “Falling wind” sound. Each hit in the pattern is progressively faster, like a bouncing ball. The dynamic transitions as well from a powerful pulse to a rumbling roll. Accelerando, but more to it than that.

23 Rafu Shimpo (2020) - https://rafu.com/2020/10/obituary-kumiko-tanaka-artist-and-backbone-of-s-f-taiko-dojo/

24 George (2018) - https://www.sleek-mag.com/article/polish-poster-design/

25 Pendergast & Pendergast (2007). Alternatively, for a quick, accessible biography, see Encyclopedia.com entry on Stan Sakai - https://www.encyclopedia.com/arts/culture-magazines/sakai-stan

26 Most of this information can be found in a talk by Rev. Mas and Johnny Mori. https://youtu.be/QSPsNZ5fDhU

27 As Rev. Mas tells it, they formed as a Buddhist study group and started with chanting. The choice of the name Kinnara was a bit of a mistake, as the Gandharvas are the celestial chanters. Kinnara would become a very fitting name, however. https://youtu.be/QSPsNZ5fDhU?t=350

28 In the field of machine learning, Prototypical Networks are algorithms that incorporate a number of examples to create a new, prototypical example used to represent a entire class in order to sort new information.

29 The Associated Press (2021) - https://www.npr.org/2021/07/27/1021144933/georgia-man-pleading-guilty-to-4-of-8-atlanta-area-spa-killings

30 The Associated Press (2022) - https://www.npr.org/2022/09/14/1123039224/serial-podcast-adnan-syed-murder-conviction

31 Koenig (2022) - https://serialpodcast.org

32 San Jose Taiko originally started as “San Jose Taiko Group” and were based out of the temple before becoming an independent non-profit in 1982.

33 Recorded music is the mode.

34 See Reviriego and Merino-Gómez (2022) for discussion and examples of how these programs interpret prompts in different languages.

Works Cited

General online references on Ukiyo-e used in this piece, not cited in-line

Blood et al. (2002), Library of Congress exhibit documentation; https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/ukiyo-e/intro.html

Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art (2004), essay; https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/plea/hd_plea.htm

Szczepanski (2019), Thoughtco article; https://www.thoughtco.com/what-was-japans-ukiyo-195008

V&A South Kensington (2020), “Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk” Exhibit; https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/japanese-woodblock-prints-ukiyo-e

Korenberg (2020), British Museum online exhibit ; https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/great-wave-spot-difference

Fiorillo (2000-2021), “Viewing Japanese Prints” webpage; https://www.viewingjapaneseprints.net/texts/ukiyoe/intro_osaka.html

Heckmann (2022), Studiobinder article; https://www.studiobinder.com/blog/what-is-ukiyo-e-art-paintings/

References

Bastian, M. (2022, July 4). DALL-E mini becomes Craiyon and hopefully the confusion stops now. The Decoder. https://the-decoder.com/dall-e-mini-becomes-craiyon-and-hopefully-the-confusion-stops-now/

Craiyon. (2022). https://www.craiyon.com

DALL·E 2. (2022). OpenAI. https://openai.com/dall-e-2/

Department of Asian Art. (2004, October). Art of the Pleasure Quarters and the Ukiyo-e Style. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/plea/hd_plea.htm

Encyclopedia.com. (n.d.). Stan Sakai. In Encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved October 12, 2022, from https://www.encyclopedia.com/arts/culture-magazines/sakai-stan

Fiorillo, J. (2000, 2021). Osaka Prints (Kamigata-e 上方絵). Viewing Japanese Prints. https://www.viewingjapaneseprints.net/texts/ukiyoe/intro_osaka.html

George, C. (2018, October 3). Discover the underrated art of Polish poster design. Sleek. https://www.sleek-mag.com/article/polish-poster-design/

Hansen, A., & Sojin, K. (Directors). (2005a, January 26). Lack of Taiko at Cherry Blossom Festival (Seiichi Tanaka Interview). http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/interviews/clips/438/

Hansen, A., & Sojin, K. (Directors). (2005b, January 27). Coming to America (Seiichi Tanaka Interview). http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/interviews/clips/436/

Hansen, A., & Sojin, K. (Directors). (2005c, January 27). Soukou Bayashi: Dedicated to the Issei (Seiichi Tanaka Interview). http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/interviews/clips/351/

Hansen, A., & Sojin, K. (Directors). (2005d, January 27). Tire Dojo (Seiichi Tanaka Interview). http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/interviews/clips/443/

Heckmann, C. (2022, August 21). What is Ukiyo-e – Artists, Characteristics & Best Examples. Studiobinder. https://www.studiobinder.com/blog/what-is-ukiyo-e-art-paintings/

Kodani, M., & Mori, J. (2021, June 27). Kinnara and the Roots of Taiko in the United States. BCA Center for Buddhist Education, Online. https://youtu.be/QSPsNZ5fDhU

Koenig, S. (2022). Adnan is Out (No. 13). Retrieved October 12, 2022, from https://serialpodcast.org

Korenberg, C. (2020, May 10). The Great Wave: Spot the difference. The British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/great-wave-spot-difference

Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. (n.d.). The Call of the East (Online Exhibit). Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. Retrieved October 12, 2022, from https://www.mfab.hu/tours/the-call-of-the-east/

Pendergast, T., & Pendergast, S. (2007). UXL Graphic Novelists (S. Hermsen, Ed.; Vol. 3). Thomson Gale.

Rafu Shimpo. (2020, October 20). OBITUARY: Kumiko Tanaka, Artist and ‘Backbone’ of S.F. Taiko Dojo. Rafu Shimpo. https://rafu.com/2020/10/obituary-kumiko-tanaka-artist-and-backbone-of-s-f-taiko-dojo/

Ramesh, A., Dhariwal, P., Nichol, A., Chu, C., & Chen, M. (2022). Hierarchical text-conditional image generation with clip latents. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2204.06125.

Reviriego, P., & Merino-Gómez, E. (2022). Text to Image Generation: Leaving no Language Behind. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2208.09333. https://arxiv.org/abs/2208.09333

Robitzski, D. (2019, March 12). The AI Nonprofit Elon Musk Founded and Quit Is Now For-Profit. Futurism. https://futurism.com/ai-elon-musk-openai-profit

Strusiewicz, C. J. (2018, January 26). Why Utagawa Kuniyoshi was the Most Thrilling Ukiyo-e Master. Japan Objects. https://japanobjects.com/features/utagawa-kuniyoshi

Szczepanski, K. (2019, October 6). What Was Japan’s Ukiyo? ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/what-was-japans-ukiyo-195008

Takiguchi, N. Y. (2020, April 2). When the Sun Goddess Hid in the Cave of Heaven: A Medicine Story from the Japanese Creation Myths. Medium. https://naokoyogitakiguchi.medium.com/when-the-sun-goddess-hid-in-the-cave-of-heaven-a-medicine-story-from-japanese-creation-myths-30b166125c32

The Associated Press. (2021, July 27). A Man Accused Of Killing 8 In Atlanta Area Spa Shootings Pleads Guilty To 4 Deaths. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2021/07/27/1021144933/georgia-man-pleading-guilty-to-4-of-8-atlanta-area-spa-killings

The Associated Press. (2022, September 14). Prosecutors move to vacate Adnan Syed’s murder conviction in the “Serial” podcast case. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2022/09/14/1123039224/serial-podcast-adnan-syed-murder-conviction

The Floating World of Ukiyo-E (Exhibit). (2002). The Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/ukiyo-e/intro.html

V&A South Kensington. (2020). Japanese woodblock prints, ukiyo-e (in “Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk” exhibit). V&A South Kensington. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/japanese-woodblock-prints-ukiyo-e

Watts, A. (1989). The Way of Zen. Vintage Books.

Wiggers, K. (2022, May 19). When big AI labs refuse to open source their models, the community steps in. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2022/05/19/when-big-ai-labs-refuse-to-open-source-their-models-the-community-steps-in/

Wong, D. (2019). Louder and Faster: Pain, Joy, and the Body Politic in Asian American Taiko. University of California Press.

In the sprit of normalizing non-literary sources of knowledge and the importance of personal histories, I would like to state that my grandfather, Hiromu “Bill” Wada, was a collector of woodblock prints, and was known for his taste. Though growing up around woodblock art did not specifically teach me about the history or process of their production, it deepened a personal familiarity with the subject matter that extends, in some dimensions, beyond an online or literature search.